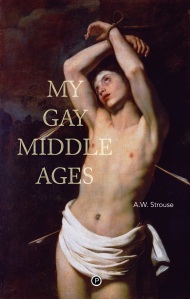

A serendipitous juxtaposition on my Twitter feed yesterday: an essay in the New Statesman called ‘No-one was “gay” in the eighteenth century’*: why we must not rewrite history with today’s terms’ and an announcement from punctum about the publication of this book:

The New Statesman essay is not arguing that no-one was same-sex-attracted in the eighteenth century, but that we should not use contemporary terms to describe same-sex-attracted people from the past. It argues that sexual identities are historically contingent and change over time, and that we should be sensitive to this. This is, of course, true – to be a prostitute in the eighteenth century means something different from being a sex worker today – but it’s every bit as true of mainstream, non-marginalized identities. To be married means something very different in Jane Eyre (Reader, I married him) than it does in Twilight. To be a woman means something very different in fifth-century Athens or first-century Rome than it does today.

The philologist George Steiner wrote in After Babel that

when we read or hear any language-statement from the past… we translate. Reader, actor, editor are translators out of time… [and] the time-barrier may be more intractable than that of linguistic difference. Any bilingual translator is acquainted with the phenomenon of ‘false friends’ – homonyms such as French habit and English habit which on occasion might, but almost never do, have the same meaning, or mutually untranslatable cognates like English homeand German Heim. The ‘translator within’ has to cope with subtler treasons. Words rarely show any outward mark of altered meaning. (p.28)

Words like ‘man’, ‘woman’, ‘married’, are just this kind of false friend, subtly betraying us into anachronism. As we read these words in past texts, we translate them into their contemporary English homonyms ‘man’, ‘woman’, ‘married’: we ‘rewrite history in today’s terms’. We read anachronistically, and this anachronism, this translation across time, creates affective, emotional, and intellectual bridges into the past for us: it opens up ways for us to find ourselves in history, to imagine (ourselves into) other worlds.

Calling same-sex-attracted people from the past ‘gay’ is also an act of translation – it translates a gendered/sexual/socially constructed identity term from one “language” or cultural/historical system into another language. It’s a more visible act of translation, though, because the terms being translated are not homonyms. Like all translations, it is inexact, but indispensible for the making of connections, and for opening up access to texts.

In Convolute N of The Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin develops an image of the historian as the counterpart of the Angel of History from ‘On The Concept of History’. The Angel of History has the wind of progress caught in his wings, and although he wants to go back into the past and rescue it, he is blown back, ceaselessly, helplessly, into the future. The materialist historian is sailing a boat; where the angel cannot move his wings, the historian can set his sails and thus navigate the winds of world history.

What matters for the dialectician is to have the wind of world history in his sails. Thinking for him means: setting the sails. What is important is how they are set. Words are his sails. The way they are set makes them into concepts. (p.473)

Words are his sails. Words – like gay – are the way we navigate historical difference, the way we access the past through acts of translation, which are also (for Benjamin, and for me) acts of rescue.

When we argue that ‘no-one was gay in the eighteenth century’, we are making hypervisible the acts of temporal translation which underlie all readings of past text – but only for identities which are marginalized in the present day. Meanwhile, identical acts of translation of/for privileged/mainstream identities – men, women, married – remain invisible, unremarked, unrebuked.

That’s bad history.

*Isn’t that title gross? It sums up the article – completely misleadingly – in such a way as to make it appear complicit with the most conservative and homophobic strands of contemporary thought: a world without gayness is possible and we lived in such a world until very recently.

Indeed. “No one was straight in the eighteenth century” would have been just as true and have made the point a more striking way, without erasing marginal identities.

I would have thought so. (Though the other thing there is that no-one really uses the term “straight people” for people in the eighteenth century – but not because straight people are so sophisticated about their language use, just because everyone is assumed to be straight, especially when we’re being told that no-one is gay. So there’s something about marked/unmarked terms there too…)